Human memory fades. Paper crumbles. Stone erodes. Yet in the digital age, our collective memory is being reborn — preserved in vast networks of servers and databases. For the first time in history, humanity has the power to record its story in real time, on a scale never before imagined. But how do these digital archives shape what we remember? And how can open-access databases ensure that memory remains alive for future generations?

Photo by Yura Lytkin on Unsplash

What Is Collective Memory?

Collective memory refers to the shared memory and cultural heritage of a society. It is a thread that connects generations. While individuals carry their personal memories and experiences, these come together through shared narratives and symbols to form collective memory. In other words, collective memory differs from individual memory in that it is built on the shared recollections of many, converging into a common narrative. This shared memory shapes social identity and strengthens bonds between generations.

The preservation of collective memory relies heavily on museums, libraries, monuments, place names, and archives as crucial sites of memory. As studies highlight, even if collective memory is not directly tied to individual recollections, it depends on socially produced elements such as libraries, museums, monuments, and history books. In this way, societies record their experiences and values through institutionalized memory mechanisms, transmitting them across generations like a “letter to the future.”

Photo by Gnider Tam on Unsplash

Archives: Institutions of Memory

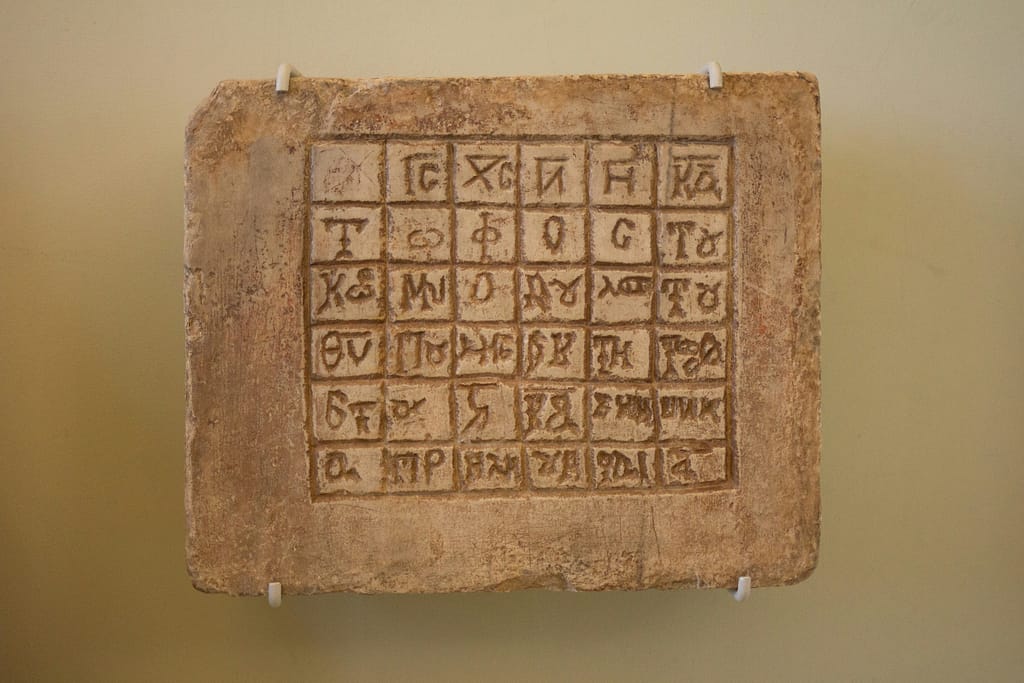

Archives protect the documents and records of history. Often called the “memory of the state or society,” they act as defenses against forgetting. Over time, as records grew in number, archives became essential to organize and preserve this knowledge for future use.

It is often said that “archives are the institutions of memory.” They provide a durability that human memory cannot match, keeping cultural context alive as well. Yet archives are not neutral. The politics of memory reminds us that what is kept — and what is excluded — shapes how we remember the past. Even in democracies, debates over archives and curricula show that the story of the past is constantly contested.

Digital Memory and Archives Today

With digital technology everywhere, archives have been transformed. Traditional documents, photos, and films are being digitized, and much of today’s content is born digital. Millions of pages, images, and audio files now sit on servers and cloud platforms. This makes storage and access easier and faster, but it also brings new risks.

The fragility of digital memory: It may seem that online content lasts forever, but digital information is surprisingly temporary. Studies show the average life of a web page is just a few months. Old links often lead to error pages (link rot) or to changed content (content drift). For historians, this creates serious problems: references disappear, and gaps open in the historical record.

To avoid a potential “digital dark age”, societies must adopt strong preservation strategies that ensure digital content remains accessible and reliable.

“Archives are the guardians of memory. They allow societies to learn, evolve, and heal.”

— Verne Harris (Nelson Mandela Foundation)

Digital Memory in Practice: Databases and Artificial Intelligence

The massive growth of digital archives has made database systems and artificial intelligence (AI) essential for managing them.

- Database systems form the foundation.

- Relational databases (SQL) organize data into structured tables, ideal for preserving archival metadata.

- NoSQL databases (like document or graph databases) allow more flexibility, especially for multimedia or irregular data such as videos, images, or social media content. Graph databases are particularly strong in showing connections between people, places, and events, much like human memory itself.

- Metadata is what makes memory searchable. Standards like Dublin Core or MARC allow archives around the world to be compatible and integrated into large platforms like Europeana or the Digital Public Library of America.

AI tools are now crucial:

- Automatic tagging: AI can scan documents and photos to add names, places, and topics.

- OCR and speech-to-text: These turn scanned text or audio into searchable content.

- Semantic search: Powered by NLP, it allows natural questions like “letters from nurses in World War I” instead of exact keywords.

- Summarization and clustering: AI can digest huge archives, highlight patterns, and group related content.

- Restoration: Machine learning helps restore damaged photos or clean up old audio.

In this way, AI becomes a co-curator of memory, helping us not only store the past but also understand and retrieve it more effectively.

Shutterstock AI Generator’s Mosaic Image

Open Access, Open Memory

Digital archives are most powerful when open to the public. Closed archives limit memory to a few experts, while open-access archives democratize it. UNESCO emphasizes that open digital platforms are a unique chance to preserve and share collective memory.

Projects like UNESCO’s Memory of the World program aim to digitize and share valuable records worldwide. The idea is simple: “The best way to preserve knowledge is to share it.” The more widely information is copied and accessed, the safer it is from being lost.

Of course, open access raises concerns. Some institutions fear loss of control or misuse. Infrastructure and resources are also challenges. But partnerships between large organizations, local libraries, and civil society can overcome these issues.

The Internet Archive: The Web’s Memory

The Internet Archive, founded in 1996, aims to give “universal access to all knowledge.” It’s Wayback Machine now holds over 835 billion web pages, allowing users to revisit deleted articles, vanished websites, and changed online content. Researchers, journalists, and even courts rely on it.

Legal battles, especially around copyright, have created challenges, but they underline the Archive’s importance: without it, much of the web’s history would disappear.

Wikipedia: Collective Knowledge in Action

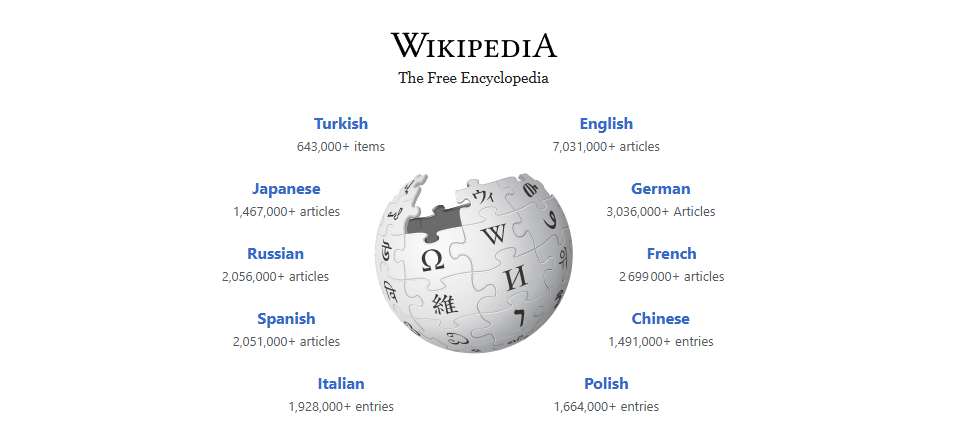

Wikipedia is another key part of digital collective memory. Built by millions worldwide, it is more than an encyclopedia — it is a living, evolving memory platform.

Available in 350+ languages, it allows societies to record their histories in their own voices. Projects in Indonesia (digitizing palm-leaf manuscripts) or Ukraine (documenting cultural heritage during war) show how Wikipedia empowers local communities to preserve memory. Its open discussions and revision histories make it transparent and dynamic, ensuring memory remains plural and participatory.

Digital Archives from Türkiye and the World

Around the world, innovative digital archives — from NFTs to open-access libraries — are ensuring that the stories of our past remain alive for future generations.

- Meta History: Museum of War (Ukraine) — Launched by the Ukrainian government in collaboration with artists, this blockchain-based digital museum captures the daily reality of the war through NFT artworks. Beyond preserving memory in a groundbreaking way, the project channels its proceeds to support war victims — combining cultural remembrance with humanitarian aid.

- Starling Lab & USC Shoah Foundation (USA) — Preserving Holocaust testimonies on blockchain across thousands of servers to fight denial.

- Europeana (EU) — A digital library combining collections from hundreds of European museums and archives, creating a shared cultural atlas.

- Trove (Australia) — Digitizing historic newspapers and broadcasts; volunteers help capture immigrant histories.

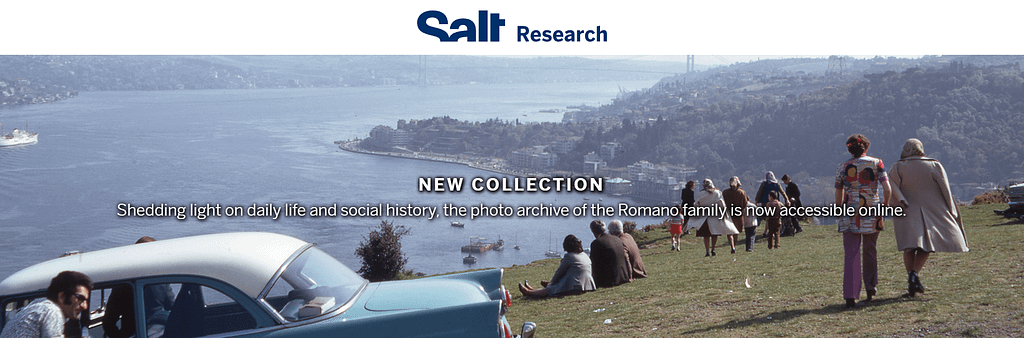

- SALT Research (Türkiye) — Based in Istanbul, this institution has digitized over 2 million documents, including 19th- and 20th-century periodicals, maps, and visual collections, and made them freely accessible. It stands as one of the most powerful platforms for opening Türkiye’s collective memory to wider audiences.

- Aizanoi Ancient City NFT Project (Türkiye) — Digitizing cultural heritage like the Temple of Zeus as NFTs to both preserve and fund archaeological work.

- Mukurtu CMS (Global) — An open-source system allowing Indigenous communities to digitize heritage under their own cultural protocols.

Salt Research Official Website

Challenges and the Road Ahead

While digital archives offer unprecedented opportunities, they also face significant challenges:

- Technical and financial sustainability: Maintaining digital archives requires infrastructure, funding, and expertise. Even giants like the Internet Archive depend on support to avoid collapse.

- Copyright and legal barriers: Many 20th-century works remain under copyright, limiting access. Government records may also face classification restrictions.

- Privacy and ethics: Archives often contain sensitive or painful histories. Balancing transparency with respect for personal rights remains critical.

- Information overload and accuracy: As archives grow, risks of misinformation increase. Rigorous metadata and expert oversight are essential to avoid distorted narratives.

- Cultural representation: Western cultures dominate much of the digital archive landscape, leaving minority and local voices underrepresented. Initiatives like Wikimedia’s language support and Google Arts & Culture aim to bridge this gap.

Encouragingly, global cooperation is rising. UNESCO calls on states to preserve digital heritage, while national libraries develop preservation strategies and open-source tools. Together, these efforts form a global memory movement.

“Without memory, there is no culture. Without memory, there would be no civilization, no society, no future.”

— Elie Wiesel

Conclusion: Building the Memory of the Future

For the first time in history, humanity has the tools to preserve its past on a massive scale. But this comes with responsibility. Database archives and digital memory will form the foundation of what future generations inherit.

Thanks to open-access initiatives, from old letters and newspapers to today’s digital culture, we are building a rich and inclusive record. As UNESCO reminds us: “The best way to preserve knowledge is to distribute it as widely as possible. Open access, open formats, and open participation keep knowledge alive.”

To keep our collective memory alive, we must not lock it away. We must share it, multiply it, and pass it forward.